If You Build It

In college, I studied cognitive science, which means I studied how input from our 5 senses gets electro-chemically translated into perception that our brain can use. One of the most powerful ways we learn (which is a ‘change in understanding’) as we navigate the world is by detecting aberrations in our sensory fields.

This means that it’s easier for people to point out problems they see than to create something new, which explains the proliferation of armchair critics in basically everything on the internet. No one needs to scan the terrain for tigers anymore, so we’ve turned our highly-tuned evolutionary systems onto others’ ideas which, if used properly, could be a beautifully useful thing if we weren’t always tripping over the egos that developed alongside that same system.

Justin’s party trick: he can name a cognitive bias or a law for pretty much any concept you throw at him. I recently shared this idea with him- the idea that I feel compelled to share my half-baked process with the world. “Oh yeah. Cunningham’s Law.”

Preach the falsehood to know the truth.

Exactly.

How does this relate to the urgent task of drying seaweed, which is widely known as one of the most head-scratching bottlenecks the industry faces? It means that I know I have to come up with something and then put it out there into the world in the hopes that you might see it and be hungry to review it. The point of this post is to draw out all of you whip-smart critics out there to critique what I’ve laid out because it’s cognitively easier to pick apart someone’s existing idea than to create something new from scratch. Might as well capitalize on it, right?

Each grower we work with has unique challenges and strengths in their kelp program. Some enjoy a direct working relationship with a township that can construct a greenhouse, which we’ve been grateful to support. Others do fine with a smaller greenhouse. Others will land massive amounts of kelp soon, and a greenhouse won’t do- but we aren’t yet to the point of needing a large-scale machine.

At this stage of kelp in NYS, I think the town/nonprofit model to support both non-profit and for-profit progress is the strongest model. NYS is different because we’re not focused on the commercial industry. We want this stuff to be accessible to everyone. It’s a big sandbox.

Back to kelp drying. Some of you may remember my husband and I as the ones back in 2020 who shoved kelp into our own personal clothes dryer on low-heat air-dry to see what would happen.

(Fun fact, and I’ll put this out there for those of you who are wildly curious but too proud to ask: if you tumble it on air-dry, you get this really cool, very strong, leather-like rope consistency. And hey, it’s yet another end use after all!)

As someone who was raised to put a roof over your head if you needed one, we designed a drying structure in our front yard. It wasn’t sturdy enough to hold the weight of the kelp, and you could only dry 20’ or so at a time.

A few months ago, I bolted out of bed at 5am the morning after spending an evening with Sue Wicks, getting fired up about her vision, memories of our funny wooden setup in our front yard in 2020, the tidy pancake of krill in the lint catcher of my dryer, and designed something again.

2 40’ shipping containers with a canopy overhead. This will get the kelp 70-80% dry. Run the kelp longlines along the red lines drawn below, sturdy hooks along the top edges of each shipping container. Then, once it’s easier to handle, you bring it inside to the shipping container (pictured right) which frees up your space for another batch outside. Each row is spaced 1-2’ apart.

Knowing what I know about kelp ((1) it’s very hard to get completely dry on its own (2) most folks won’t be willing to pull it inside into their air-conditioned bedroom in crates like we were), I know we need to find a way to take it from 80 to 100%. I’m so grateful to The University of Arkansas for openly sharing their work with the world- a shipping container dehydrator for hops, which has been said to be roughly similar to kelp as it relates to the drying process. So you run the 80% dried kelp along the light blue lines on the right shipping container, get it to 100%, chop it off, put into containers, and store in the left shipping container for storage. This hybrid approach capitalizes on the lower energy sources to get you most of the way, and mechanical efforts to carry you to the finish line. Some of it can be sold as whole-blade or chopped (once it’s dry enough it breaks apart easily)- a smaller portion of it could be brought back out to grind or made into foliar spray, extracts.

Did you think I was exaggerating when I said I dragged crates of kelp into my own bedroom?

The storage unit on the left can store equipment and product, which would dry to 10% of its weight.

This process is not for food use, but it could later be tailored for food processing, like adding in UV lighting inside one of the containers as a bacterial kill step. (Do you see what I did there? If I ruffle someone’s feathers about food safety with this blog post, they’ll be quicker to come to the table with their concerns than if I try to email them with my request for input to design something from scratch.)

You could also add all kinds of bells and whistles like solar panels along the top to offset the energy needed by the grinders. Think of it: they add power back to the grid all year, minus the 2-3 weeks when power is needed.

Then comes “OK, but what are you gonna do with the kelp?” Well, if I had it my way, it would get stored in large quantities for a minute because we need to ramp up supply for markets to take notice and interest. You need a LOT of kelp to bring serious industry. Like, a lot. You also need to grow a lot to start to make any kind of impact on carbon and nitrogen uptake.

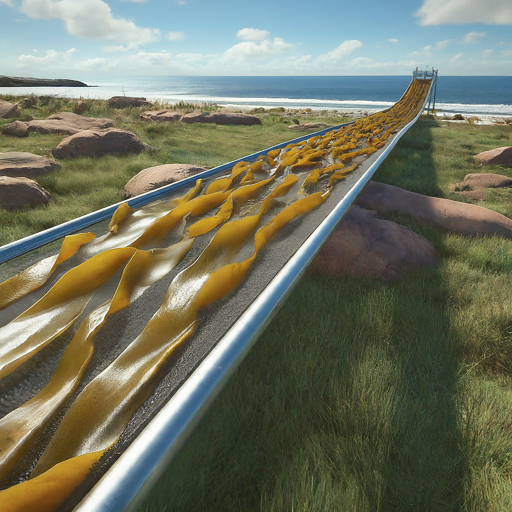

Lately, I’ve been bouncing around in the echo-chamber of possibility between AI and Google, researching dryers (Gelgoog, Alvan-Branch, Sirputis- others?) and then taking breaks to fashion my own funny setups with AI prompts to break me out of my funk of what has been done before and what’s possible.

To be continued.